Approaching the Residual

This article arose from the encounter and dialogue between a Humanities researcher who was born in and worked his entire career in Łódź (Tomasz Fisiak) and an Australian-based researcher encountering the city for the first time (Philip Hayward).Hayward’s initial input was to comprehend the city’s civic symbolism and ‘missing’ river systems and, in a Brechtian sense,1 make these ‘strange’ in order to activate Fisiak’s deep knowledge of the city and its history. Our subsequent attempts to understand the residual traces of rivers in and around the city were inspired by two studies of Łódź’s Jasień River (Jędruszkiewicz & Piotrowski 2013; Szkurłat 2015) and by Kobojek’s (2017) account of Łódź’s early river history (discussed in detail in the subsequent section). Other notable research that aided our understanding includes Paul Talling’s (2011) volume London’s Lost Rivers and the collaborative research by Toso, Spooner-Lockyer and Hetherington (2020) on the St. Pierre River in Montreal/Tiohtiá:ke.2

Toso, Spooner-Lockyer and Hetherington address the manners in which various waterways have been rendered ‘ghostly’ as a result of their submergence beneath concrete, asphalt and other human constructions and/or by their frequent channelling through pipes. The authors’ approach was particularly appealing to us through its deployment of Derrida’s (1994) notions of the spectre and of ghostliness to focus on how such traces can disrupt Anthropocene modernity. Discussing the ‘varied connections between landscapes, archaeology, folklore, and the spectres of the past’ and, more generally, of hauntological approaches derived from Derrida (1994), Paphitis (2020: 2) emphasises that ‘places are not only haunted by “conventional” ghosts, other revenants or non-human, supernatural beings; hauntings are also personal memories, collective histories, or physical remains.’ Citing Gordon (2008: 9), Paphitis emphasises that all ghosts are intrinsically ‘of the present, and can only make their social meaning through direct engagement with others in the present.’ Characterising hauntings as ‘often about the engagements between the human and more-than-human,’ she contends that ‘the examination of the theme of haunting dissolves lines between the “natural” and “cultural” and reinstates voices of overlooked agents’ (2020: 2).

We concur with this contention and find alignment with Toso, Spooner-Lockyer and Hetherington (2020), who also assert that, ‘the figure of the ghost disjoints both time and being, disrupting the relations between past, present and futures, hovering on the edge of being’ and manifests as ‘a presence-absence that transverses spatialities and temporalities’ (2020: 2). Acknowledging Derrida’s (1994) characterisation that such disjunctures require mourning and the assumption of contemporary responsibility for past actions (1994: xviii), Toso, Spooner-Lockyer and Hetherington (2020) identify that their study involved them developing ‘an ethics of hauntology; that is, a set of obligations to both past and future generations’ that recognises that ‘ghosts unsettle the time of the Anthropocene, not just as a time of rumbling disaster but as a time littered with the disasters of the past’ (2020: 2).

In a similar (albeit more poetic) vein, Gan, Tsing, Swanson and Bubandt (2017: G2) characterise that the ‘winds of the Anthropocene carry ghosts — the vestiges and signs of past ways of life still charged in the present … the traces of more-than-human histories through which our ecologies are made and unmade.’ In what follows we both explore material traces of river courses and investigate the ‘charged’ ‘vestiges and signs’ of their social, economic, and cultural aspects in civic and popular culture. An aspect of our study addresses signage and bodily decoration, illustrating how the city’s historical elements persist in ways that interact with the present, potentially reinvigorating it. Christian Fleury’s cartographic research and representations complemented this by enabling us to see the traces of a fluid past beneath the concrete and asphalt that dominate the city and to reimagine its presence and negotiate the ghosts we encountered.

While they do not expressly state it, Toso, Spooner-Lockyer and Hetherington’s (2020) approach complements the concept of the ‘personhood’ of rivers that has been promulgated over the last decade. This concept was first advanced by Christopher Stone (1972) in a law journal paper that proposed that legal rights be given to ‘forests, oceans, rivers and so-called “natural objects” in the environment’ (1972: 456). This proposal was drafted to overcome the issue that flowing bodies of water were not rights-holders, under US (or, then, any other) law and thereby have no legal ‘standing’ and no recourse to challenge polluters, aside from any that might arise from individuals or communities acting on their own behalf (1972: 459). While Stone’s (1972) proposal lay dormant for several decades, several Indigenous and environmental activists have recently embraced the challenge and successfully campaigned for recognition of riverine personhood. The first notable victory was for New Zealand’s Whanganui River (Hutchison 2014), followed by Bangladesh’s ground-breaking decision to grant all its rivers personage in 2019 (Sohidul Islam & O’Donnell 2020). From this school of thought, Anthropocene violence against rivers (in the form of redirection, constriction, burial etc.) is directed at entities that can be considered personable, facilitating our compassionate engagement with them. In a related sense, empathising with, and advocating for submerged rivers involves a recognition of what the River Cities Network Manifesto (2022) refers to as, ‘the integrity of rivers as complex aquatic-terrestrial systems that merit respect and care.’

We also parallel Talling (2011) — who has gone on to organise a series of exploratory walks following the publication of his 2011 book — and Toso, Spooner-Lockyer and Hetherington (2020) in terms of their practical approach to sensing and rediscovering river courses. This has entailed exploratory ‘walkings with’ above ground traces of water routes that involved a variety of perspectives (historical, engineering, cartographical, socio-economic, etc.) and enabled an ‘ontology’ that emerged ‘within a multitude of practices and discourses, continually constituted and reconstituted through its relations with others’ (2020: 3). Our research and reflection were premised on similar searches, pursuits and encounters undertaken between October 2022 and November 2023. While acknowledging our debt to the above authors, our project had significant differences, principally that we were prompted to investigate a history that was manifest, albeit by proxy, in plain sight in the name and public symbolism of our subject city. Indeed, as discussed in Section II, one of the most curious aspects of our study is our observation that the ghosts of Łódź’s riverine past have been manifest in the city’s public visual culture in inverse proportion to the near invisibility of actual waterways in the city’s modern urban fabric. This perception led us to reflect more creatively on senses of civic identity, riverine personhood, and spirits-of-place in modern Łódź and how those might affect a city’s re-engagement with its waterways.

Łódź and Its Disappearing Rivers and Streams

Numerous river valleys constitute an intrinsic part of the natural and cultural landscape of Łódź, and are an important witness to the history of the city. They should therefore constitute an essential element of the quality of the urban space and the city’s identity and be the object of utmost care of the residents (and managers of the city), striving to preserve their timeless values. Unfortunately, the rivers of Łódź that once played a crucial role in the creation and initial industrial development of the city, are now on the margins of the city’s spatial planning approach, and have a low presence in the memory and awareness of the residents. The literature devoted to these man-river relationships includes a metaphor describing this situation as: the city that turned its back to the river. (Szkurłat 2015: 47)

Łódź, located in central Poland (Figure 1) is the country’s fourth largest city. The present-day city grew from the medieval village of Łodzia, on the banks of the River Łódka.3 These names are variations on the noun łódź, the Polish word for boat, and reflect the fundamentally riverine orientation of the early settlement. Like Poland, more broadly, the area around the Łódka River experienced serial subjugation by foreign powers: by Prussia in 1793–1806; France in 1806–1815; the Russian controlled Polish Congress in 1815–1915; and German control in 1915–1918. Following a brief period of Polish independence, Łódź and Poland were occupied by Germany again in 1939–1945 before falling under Russian control until the Solidarność movement led the Polish to overthrow Soviet domination in 1989. The present-day city has its roots in a major industrialisation of the area that commenced in 1825, with establishment of the city’s first cotton mill. By the 1840s, Łódź was the largest producer of textiles in the Russian empire and its expansion continued through to the 1890s. By the early 20th century, Łódź was one of Europe’s most populated cities with its population numbering around 633,000 in 1935. The population peaked in 1990, at just under 850,000 and has declined in the post-Communist/European Union era to around 683,000 in 2019 (Szpakowska-Loranc and Matusik, 2020: 6).

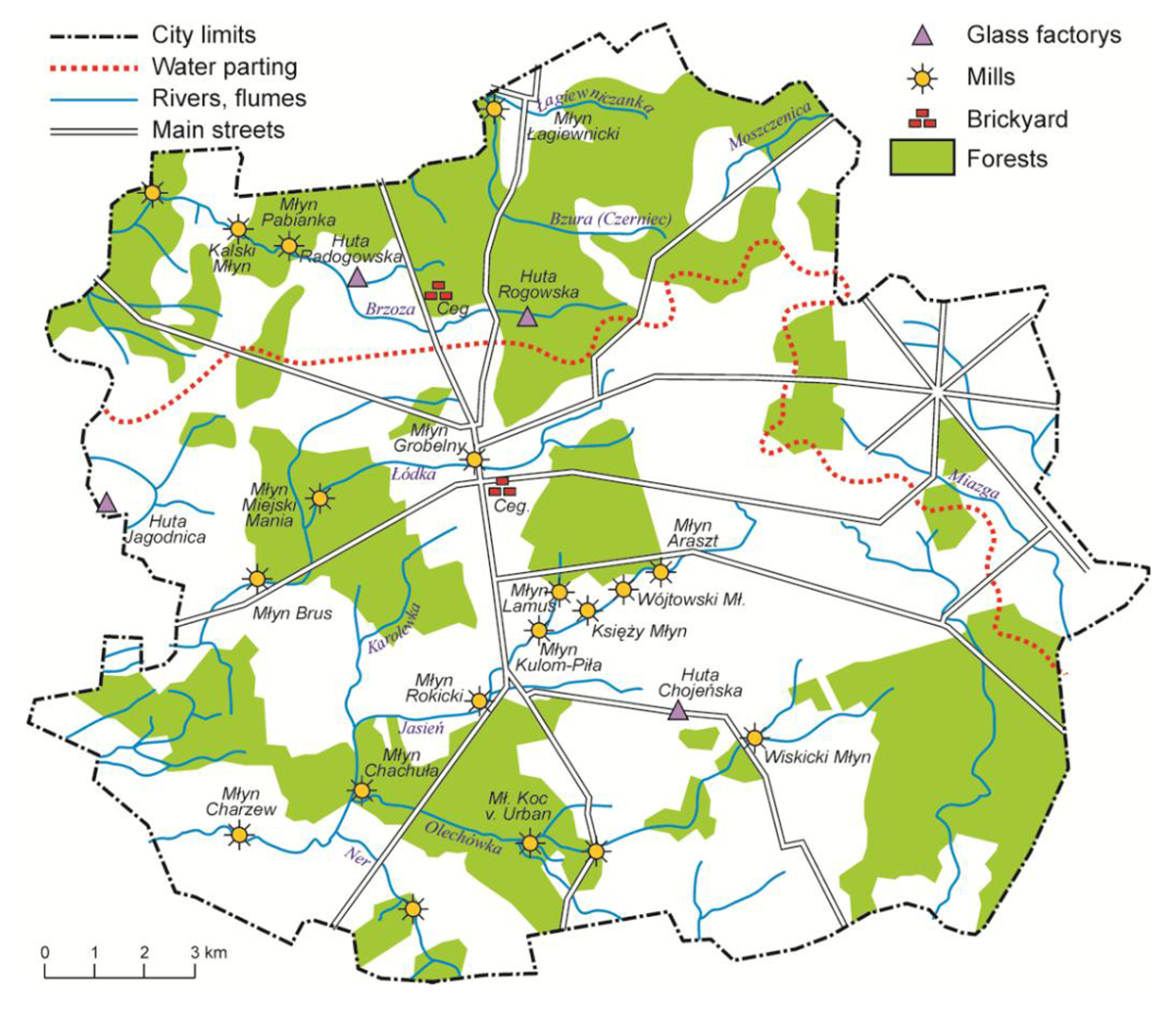

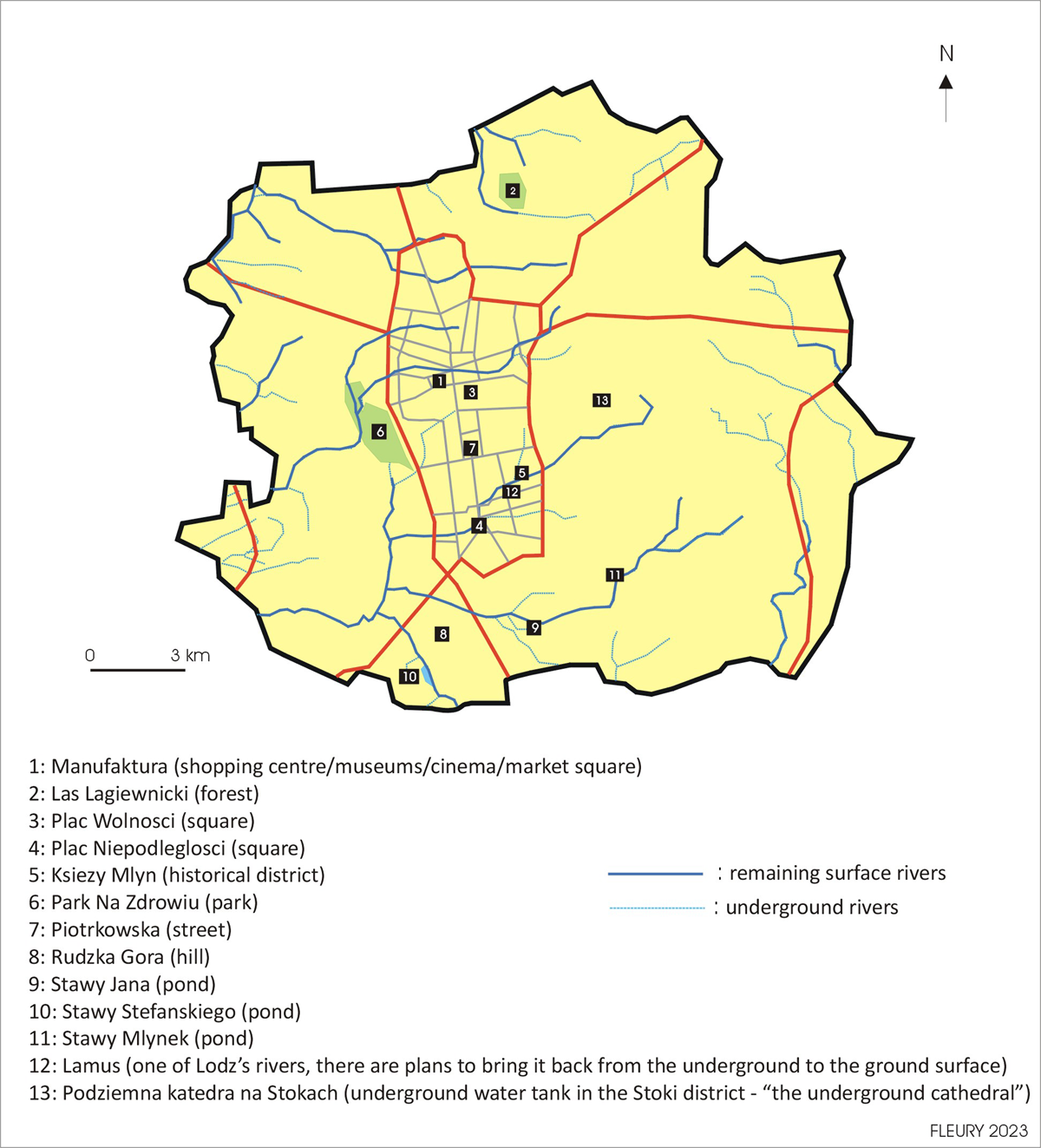

Unlike other major Polish cities such as Warszawa (Warsaw), which was established on the banks of the wide and easily navigable mid-section of the Vistula River, Łódź developed on an area of relatively high land at the juncture of the watersheds of two major river systems: the Vistula and Oder. Łódź’s present day urban area rises to a peak of 280 metres above sea level in the central eastern area of the city and declines to 160 metres at its south-western point and 230 metres at its eastern edge. This topography has determined the points of origin and directions of flow of its rivers, with most flowing approximately south-west as tributaries to the River Ner and with the majority of remainder flowing north or east (Figure 2).

The quotation from Elżbieta Szkurłat (2015) that opens this section is of particular relevance to us, as it identifies the manner in which the river valleys that comprise the natural, underlying landscape of Łódź can be understood (in personhood terms) as an ‘important witness’ to recent changes in the area and the impact of the Anthropocene more generally. Her study focuses on the Jasień, one of several small rivers that flow west or south-west towards the Ner, and as she details (2015: 49) it was the main source of potable water for the sparse, pre-industrial, population of the area and was subsequently the site of the area’s first watermills in the early 1800s:

The abundant waters of the local rivers and streams proved particularly useful. The energy produced by falling water was used to power factory devices. The river also played another, important role in the textile industry: large volumes of clean water were used in the process of fabric whitewashing, rinsing, softening and dyeing. (Szkurłat 2015: 50)

As industrialisation intensified in the late 1800s, the Jasień became a conduit for the disposal of effluent and sewage, and parts of the river’s course were covered over in new industrial developments to conceal the water flow. As Kobojek (2017: 11–12) has described:

A contaminated river posed a threat and was unattractive within urban space, which is why works begun to regulate them and to construct a sewerage system. First, the pond within the valley of the Łódka in the city centre was buried and the river was partly enclosed in a subterranean canal (1917). In 1925, the construction of the sewerage system began. At that time, the natural river network was included in the sewerage system. All the rivers within the industrial 19th century part of the city (today’s city centre) were concealed in subterranean canals ... Some channel sections and many older reservoirs were buried. In the first half of the 20th century, rivers disappeared from the cityscape altogether and in the second half they even disappeared from people’s memory … As a result of directing former rivers into subterranean canals, new flat and low-lying areas formed. Quite soon they were all utilised. Usually, they were used for transportation infrastructure, e.g. wide streets … important road junctions, tram routes… a tram depot, but also … residential structures. Thus, the fact that there once were some rivers was soon wiped clean from the inhabitants’ memory. (2017: 11–12)

But while individual memories may have been largely effaced, traces of the area’s riverine past persist in local place-naming. In his illuminating, essayistic work Rzeki, których nie ma (‘Rivers that do not exist’), Maciej Robert (2023) provides a list of places whose names are indicative of their riverine background. For instance:

Two place names that derive from the Polish term źródło (‘spring’): źródliska Park (built on the Jasień river) and źródłowa Street (which follows the course of two rivers, the Łódka and Stoczanka).

Podrzeczna (which can be loosely translated as ‘the street under the river’): one of the oldest streets in Łódź’s old town, built on the banks of the Łódka river, which has been canalised since 1918.

The Sikawa district (whose name implies springs). (Robert, 2023: 33).

Some other places that retain similar designations include Nad Jasieniem Street (situated on the old course of the Jasień river) and Zimna Woda Street (whose name translates as ‘Cold Water,’ and which crosses the course of the river of the same name). Another notable example is Wodny Rynek (the ‘Water Market’), the vernacular name for Plac Zwycięstwa (Victory Square), a small area situated in close vicinity to źródliska Park. Wodny Rynek was its official name until 1945, when the victory appellation was introduced. Despite the latter, the communist regime did not change the name of the street next to the market, which retained its pre-war appellation, Wodna (‘Water’) Street.

The invisible presence of rivers in Łódź is also demonstrated by various surface features. Interviewed by Adamczewska (2023), Maciej Robert identifies two streets in Łódź’s old town, Wolborska and Drewnowska, both of which were constructed above the canalised Łódka River. Their meandering shapes notably distort the grid street system so typical of Łódź city’s centre. Robert also mentions a remaining part of the bridge over the Jasień River in Wólczańska Street that looks completely out of context in its current form (Adamczewska 2023). He also relates that Apsys, the company responsible for converting a former industrial site into the Manufaktura retail and leisure complex that opened in 2006 (Figure 3, key item #1), wanted to uncover the stretch of the Łódka River running beneath it, but found that its stench was unbearable (due to the amount of wastewater that continues to feed into it) (Adamczewska 2023). As a result, they opted for a line of fountains following the course of the river instead (Figure 4).

Until the late 20th century, the city’s neglect of its riverine history remained largely unacknowledged, unquestioned, and unchallenged. More recently, several research and policy initiatives have attempted to re-engage with the past and postulate a different future. In this context, the aquatic associations of the city’s name, i.e. boat, can be seen to have paled to near invisibility in a similar manner to that of Ann Arbor (Michigan, USA), whose present-day urban form has little resonance with the arbors (groves) of trees that clustered the area when European settlers began to develop it in 1839. Even during the times of forgetting, Lódź’s riverine identity persisted in its civic logo, which provided proxy symbolism for the absent waterways.

Metropolitan Symbolism

The city’s first and most obvious riverine association relates to its name. As previously identified, łódź is the Polish term for boat and the city grew from the village of Łodzia, located on banks of the River Łódka, a nest of related place-names that reflect the area’s riverine aspect. While relationships between places’ names and aspects of their locale are variable (rather than determinative) (Ainiala & Östman 2017), this cluster of associations around the name and context of the city has been reflected in its civic imagery by virtue of its heraldic shield featuring a boat as its sole motif. This is a more complex visualisation than might first appear. Heraldry is an interpretative rather than representational practice and its hermeneutics are complex (see, for instance, Tiller 2007). One commonly used design tactic is the cant, a visual allusion to a subject’s name. This practice has resulted in an extensive canon of illustrative visual symbols. One notable aspect of heraldry is that heraldic designers have often operated at some distance from the circumstances and personalities of their subjects — be they individuals, families, cities, or corporations. They, therefore, frequently use motifs and formulae drawn from heraldic traditions and/or broader patterns of visual culture, rather than any careful address to the particularity of clients’ nature or circumstances. In other words, there is no evidence that the designer who drafted Łódź’s metropolitan shield had any knowledge of the relevance of the River Łódka to the etymology of its place name, nor any inclination to represent a type of watercraft representative of those used in, or around the city. In this manner, the etymology of the city’s original place name proved deterministic on the city’s heraldic rendition and preceded the massively reduced prominence of riverine environments during the city’s development in the 19th and 20th centuries. The boat image can thereby be considered as a refracted impression of past environmental circumstances retained in an ongoing play of symbols and representations.

The civic shield features a small, shallow-draft boat with high prow and stern and a single wooden oar (Figure 5a), a design that suggests its use on sheltered inland waterways. The boat image also features on the city’s flag (which features the city’s shield on a yellow and red background) (Figure 5b) and in symbols and logos of other local organisations as diverse as the Politechnika Łódzka (known in English as Lodz University of Technology) (Figure 6a) and, in juxtaposition with the Catalan flag, Łódź’s FC Barcelona fanclub (Figure 6b).

One of the most congruent contemporary associations of civic symbolism and riverine environments occurs outside of the city centre (the main focus of our analysis) on the Jasień River as it flows through Rokicie, a suburb to the south-east. While the river’s banks have been partially stabilised, the richness of shrubbery and trees growing along the river is evident, houses are few and far between, and waterfowl frequent the area, enhancing its bucolic aspects. The area’s particular charm for walkers and residents is that within 500 metres there are two confluences, with the Ner (Figure 7) and with the Olechówka (Figure 8), that create conducive environments for waterfowl. Even though the riverbanks are often quite muddy after rain, they are easily accessed and regularly used by pedestrians.

On the banks above the confluence of the Olechówka (Figure 8, right fork) and Jasień (Figure 8, left fork), concrete walls separate a property from the riverbanks. The walls are covered by graffiti but in prime position at their junction, overlooking the confluence, one image stands out: a crisply executed rendition of the city’s crest (Figure 9). While the artist and/or their motivations are unknown, the image appears in one of the most appropriate places in the city. Particularly in terms of the logo’s evocation of a riverine past, and any sense of irony is contingent to reading the locale off against the urban centre. Contextually, the graffiti image can be read as evidencing pride for the place and for the history the symbol evokes.

Detail of graffiti wall shown in Figure 8 above, seen from a slightly different perspective. (Photo by Marek Majer, October 2023).

Recently there has been a strikingly stylised reimagination of the city symbol in the form of a logo designed for the city’s transport organisation MPK (Miejskie Przedsiębiorstwo Komunikacyjne), where the boat’s planks are rendered as three planes receding into the distance with a thin, elongated triangular shape intersecting them, representing the oar (Figure 10a). Significantly (for our present discussion), the design can both be interpreted as an abstraction of its predecessor that less obviously represents a boat and/or as an image and suggests a dynamic flow appropriate for a transport organisation (rather than the static appearance of the civic logo). This modified symbol has also been utilised by other bodies such as the Akademia Miejskiego Podróżnika (Urban Travel Academy) (Figure 10b).

Along with these stylised public logos, one of the most striking manifestations of boat imagery in Łódź occurs in the form of a three-storey high, 600 square metre public mural on the wall of a building at 152 Piotrkowska Street, facing a car park. As Jażdżewska (2017) elaborated, public murals first emerged in Łódź in the 1960s, during the socialist era, with many representing aspects of the city’s textile industry (2017: 47). These were not maintained in subsequent decades, and many fell into disrepair. The second wave began in the early 21st century. Jażdżewska (2017: 47) has identified the origins of the Piotrkowska Street mural in the 2000 ‘Colourful Tolerance campaign, whose aim was to protest against ‘intolerance’, xenophobia and vandalism.’ The Futura Design Studio group were awarded funding to produce a mural in 2001 and its design represents areas (such as Plac Wolności [‘Freedom Square’]) in a de Chirico-like cityscape4 and includes representations of contemporary construction technologies, signalling the city’s ongoing, post-industrial transition. Most strikingly, it represents a huge boat bursting out of the pictorial space and implicitly, out of history itself, into the present (Figure 11). The boat surges forward on fabricated material waves, looming above the car park as if it is about to crash onto the dry asphalt in search of lost rivers to navigate. The image is also complex, in that its łódź is doubled. Emphasising its symbolism of the city, the boat bears the city’s boat symbol on its prow and a single oar protrudes from its side (as on the city shield), but its size and power are also scaled up by the addition of a sail, suggesting the boat’s ability to range wide.

A sense of affective engagement with civic symbols can be gained by both their prominence and the nature of their interpretation in tattoo designs acquired by residents. Tattoos have significantly increased as a form of body decoration in a wide range of Western countries over the past three decades. Armstrong, Owen, Roberts, and Koch (2002) identify three principal reasons people acquire tattoos: for aesthetic purposes (body decoration as a practice-in-itself), for individual signification (selecting designs that have particular personal relevance and thus convey a unique personal identity) and for social affiliation (choosing a recognisable symbol to signify their identification with a particular place, community and/or heritage). It is, of course, possible to deploy all three aspects through specific designs. The popularity and modification of civic symbols in tattoo designs, and discussion of the significance of this practice for local heritage and pride of/in place, has also been explored by Wasilewski and Kostrzewa (2018) with regard to Warszawa’s syrenka motif, and by Hayward (2017) with regard to Singapore’s merlion. Wasilewski and Kostrzewa’s (2018) research is of particular relevance to our study in profiling a Polish cultural practice. Identifying that tattoos are most prevalent in Poland for individuals in the age range of 25–44, the authors make a case for active engagement with the syrenka as a symbol of Warszawa being a result of the city’s highly fluid population, resulting from in-migration from other areas of the country and with new arrivals seeking to connect to an established civic identity through a ‘conscious and individual choice of belonging that tattoos help to emphasise’ (2018: 160). By contrast, Łódz has a declining population and limited in-migration. In this regard, it is likely that desire to forge a connection is less important than other aspects of identity formation.

Research on local tattoos for this article was more limited in scope than Wasilewski and Kostrzewa’s (2018) study (which used a Muzeum Warszawy image contest to garner submissions together with Instagram searches), as this article primarily involved a Google Images search alongside follow-up messaging related to that content. One clear result was that, unlike Warszawa, relatively straightforward reproductions of the civic symbol as a tattoo were limited in number.5 But, somewhat surprisingly, from the early 2000s onward there were a number of images that evoked aspects of the Piotrkowska Street mural. While these are far more limited in visibility/circulation than the aforementioned civic signage, they nevertheless merit attention for the nature of their designs and for their imaginings of Łódź’s heritage and contemporary identity. Most of these images were produced by leading Łodzian tattooist Aleksander Iwancz at Sigil Tattoo. Andrzej Gagz, manager of Sigil Tattoo provided the following context for the designs:

Łódź had a reputation for being the worst and the poorest large city in Poland. Indeed, it was very neglected and had a prominent working-class character. Living here wasn’t particularly exciting. On the other hand, for me and many of my friends from punk and artistic circles, the city’s severity was an inspiration for our own actions. We reminded ourselves of its multicultural roots and the disastrous effects of two totalitarian regimes that left their mark on it. It wasn’t particularly easy to latch onto a larger idea in Łódź. Even a wrong one because Łódź was one of a few cities to resist nationalist, racist, and xenophobic attitudes that were very noticeable in Poland at a certain period. Even the radical football patriotism didn’t gain so much acceptance here. At that time [i.e. the 1990s/2000s], many people expressed their vision of ‘Greater Poland,’ all of which stemmed from mythomania, provincialism, and blind rage that would usually find no outlet. For instance, racist flags were displayed at matches, there were attacks on those who looked different, and ultra-right-wing symbols were tattooed. To counterbalance such acts, I felt that we could rely on something different, smaller, more local, but also universally scorned, and give it a different meaning. We started tattooing dark, industrial motifs such as machine parts, gears, and landscapes with factories, and then the first ‘little boats’ appeared. It was so well-received that more and more people came to get their Łódź-themed tattoos. (Translated interview with Tomasz Fisiak, 6 November 2023)

Seven of the images reproduced in Figure 12 (a–f) show the traditional boat image of the city bearing the factory buildings that came to prominence after the covering over of waterways that had previously defined the landscape. They thereby suspend two, arguably antithetical, aspects in one image and celebrate both as key elements of city heritage, jumbling temporality by keeping successive associations in play. Two other images suggest the decay of the traditional symbolism of the city. Figure 12c shows the city boat in skeletal form, with a tree growing out of its hull and with black wash bleeding down, while Figure 12h has an even starker image of a skeleton helming a skeletal boat in an image that suggests the decline of previous riverine heritage. One of the most optimistic images uncovered by our research is that reproduced in Figure 13. This tattoo design shows the civic boat bearing factory buildings accompanied by maple branches and a large, freshwater crayfish crawling up its side. The image neatly symbolises the past, present and (one) future for the city; its riverine and industrial pasts complemented by a resurgent nature. While the three key images, the boat, the crayfish, and factory, all inhabit the same temporal instant, it is the giant crayfish that seems to be seizing the moment (and, arguably the future) as it emerges from the river and clambers upwards.

Inventive Łódz tattoos (tattoos and photographs by Aleksander Iwancz, Sigil Tattoo, 2017–2022).6

Chasing Residuals

Our first attempt to visit, apprehend, and document remaining surface stretches of rivers took place in October 2022, when University of Łódź academic Tomasz Dobrogoszcz led Philip Hayward and fellow Łódź academic Agata Handley on an inner-city river ‘hunt.’ Driving in his car we used Google Maps to try to get close to a short stretch of (above ground) river indicated in the Górniak area. After a few dead ends we parked on a patch of wasteland and approached and peered down through a thicket. From this vantage point, we saw a short, narrow channel exposed to the air after emerging from a concrete culvert and disappearing into another one about 250 metres further on. This is one of the few visible stretches of the Jasień River in the central city. The reason for its above-ground presentation at this point is unclear. While the flat concrete platforms at either side of the thin central channel are easily walkable, the distance along the stretch is short, the channel is not easily accessed from the surrounding slopes, and it is far from picturesque (Figure 14). Given its prosaic functionality, its most striking aspect is the highly securitised upriver opening (Figure 15). While its security gates may be a safety measure (to prevent people from entering passages that might rapidly fill with water), they also tantalise by locking people out from an underground network of the city’s once free-flowing rivers. Standing on the concretised bank of the channel, what was most apparent was a sense of the intervention into a natural watercourse and the concrete ‘straightjacketing’ of its flow. There was also a sense of imbalance. Shrubs had been allowed to proliferate along the banks and patches of thick grass had grown up from cracks in the concrete. Nature was reclaiming the surrounds of the river, but the concrete cloaking of the watercourse seemed resolute, determined to manage the flow it framed despite the abundance of green around it. As Philip Hayward recorded in his field notes for the day:

Peering into the gridded culvert, I wondered what kind of spirit-of-place the submerged river would have. Warszawa, on the banks of the broad Vistula, has its Syrenka, a proud, strong, fish-tailed mermaid, holding a sword aloft, symbolising the city’s victories over a series of invaders, her symbolism echoed in all manner of civic and vernacular imagery. But there are no syrenkas here. Instead, gazing into the shadowy tunnel, an image from horror cinema comes to mind — a pale, deformed creature lurking in subterranean tunnels, starved of sunlight, resentful and revengeful. A shadowy spirit-of-place, a nightmare of modernity symbolising all that has been lost, the personhood of buried rivers twisted into an unsavoury mutant (Hayward, 2022).

Other areas of exposed water channels have been engineered for specific civic purposes and their ghosts occur on different socio-cultural planes. One notable example occurs within the Bałuty district. An engineered and landscaped section of the (mostly submerged) Łódka River stretches approximately 850 metres from źródłowa Street (in the south-west) through Park Ocalałych and on to Akademia Sztuk Pięknych (the Academy of Fine Arts) (in the north-east). The water in this area is well-managed and cannot be thought of as a natural river in any conventional sense. Rather than a continuous fluid space, the water is corralled into a small pond in Park Ocalałych and a miniature lake to the north of the Academy (which the main building faces onto, giving a suitably scenic aspect). Between these points, the river is often little more than a wet, marshy cutting, deprived of a flow-through current (Figure 16). At the south-western corner of Park Ocalałych, an attractive water feature has been constructed adjacent to a memorial erected in 2009 to commemorate Poles who had saved the lives of Jewish compatriots during World War Two (Figure 17). A set of concrete steps runs down from the memorial to a pond in which an approximately rectangular area of reeds has been planted (Figure 17). Here, the city’s riverine past is displaced by a different set of associations. The reed feature evokes two linked aspects of Hebrew mythology. The first is the reed basket in which Moses was placed in a basket for safety as an infant (Bible, Exodus 2,1) and the second is the yam suph (reed sea) through which Moses led the ancient Israelites to access Canaan, the ‘promised land’ (Bible, Exodus 15, 4).

Water Management and the Restoration of Metropolitan Rivers

In their 2020 study, ‘Łódź — Towards a resilient city,’ Szpakowska-Loranc and Matusik (2020: 11) summarise the detrimental impacts of the canalisation of waterways and the covering over of much of the city’s surface:

The canalisation of most waterways due to their pollution led to the loss of one of the fundamental structure-forming and identity-related elements from Łódź’s urban landscape. Both the shape of the terrain of the Łódź agglomeration and the progressive paving of its urban space have led to a sudden outflow of water from the city and to the local flooding of suburban areas. The small waterways that remain in Łódź do not have the necessary water retention capabilities to stabilise the city’s water management situation. Excessive water consumption leads to a drastic decrease in its quality and quantity in Łódź. It is estimated that the groundwater table has lowered by from a few to around a dozen metres within the city … The progressive loss of water and the resulting difficulties with maintaining urban greenery have considerably decreased quality of life in urbanised areas (2020: 11).

The challenge of redeveloping a blue-green system has been taken up in recent years by the City of Łódź’s Environment Management Division (EMD). Early projects have included the development of a concept for blue-green infrastructure and sustainable water management in the Lamus River Valley. Plans are currently underway for uncovering the Lamus River in Kilińskiego Park as part of a major redevelopment, whose main objective is to ‘literally and metaphorically’ uncover ‘the fastest flowing river in Łódź, bringing it to the surface from a covered underground canal and allowing natural, unregulated water flow in the park’s space’ (Sztuka-Tulińska, pers. comm. 2023).7 Further projects include the restoration of the area of the Sokołówka River outside the metropolitan zone.

At the time of writing, Łódź’s EMD is also attempting to lever support for a ‘Green Routes’ project from Łódź’s masterplan for the Expo Horticultural Exhibition, scheduled to be held in the city in 2029. Aleksandra Sztuka-Tulińska, deputy director of EMD, has summarised this as:

A system of green corridors in the city based on green areas such as parks, green spaces, squares, and avenues, which are often linked to the presence of water. Building on the experiences gained at different stages of the Sokołówka and Lamus projects, we intend to continue efforts to reintroduce rivers into the public spaces of our city. This is not just to improve the aesthetics of the surroundings but primarily to restore urban ecosystems by increasing water retention, relieving stormwater drainage, enhancing biodiversity, introducing new quality to public spaces, and raising awareness among residents about the existence and historical and contemporary significance of rivers in Łódź’s urban fabric (2023).

This statement outlines a complex restorative vision for the city and its variously ‘invisible’ and ‘forgotten’ waterways. Irrespective of the results, in terms of components delivered, it signals a radical reappraisal of the value of urban waterways in the city that is in harmony with broader international initiatives.

Conclusion

Our discussions have sought to engage with the present-absent, ghostly nature of Łódź’s covered-over, inner-city waterways and the manner in which Łódź’s metropolitan logo, isolated street names and physical features have persisted as symbols of what once was. The collective personhood of Łódź’s waterways can be seen as buried but not deceased, constrained but not erased. The juxtapositions of boats and factories in tattoo designs neatly hold two historical tendencies alongside each other and give a transhistorical sense of Łodzian identity. Similarly, the graffitied symbol at the confluence of the Olechówka and Jasień rivers provides the civic image with an appropriate context and an appropriate memory referent for its symbolism. Our ‘walking with’ submerged river courses and our attempts to engage with the few above-ground stretches of these also represented a walk through the city’s Anthropocene heritage landscape, a realm of traces and suggestions scattered across concrete and asphalt where watery rumours bubble unseen beneath the surface. Throughout, we had little sense that what was lost could be in any way adequately restored but, rather, that its traces could be opened to the sky again in key locations in the manner of urban acupuncture, supporting blue-green regeneration in highly local contexts that could bring riverine flora and fauna back to urban landscapes and provide oases within the cityscape. Such ventures cannot, of course, reverse the Anthropocene in any meaningful way, but can stand against its supposedly inexorable ‘winds’ offering sanctuary islands for the ‘ghosts’ they carry along with them (Gan, Tsing, Swanson & Bubandt 2017: G2). Temporality is also significant, and even ‘weird,’ here. Buchan (2020) has colourfully contended that, in the Anthropocene:

[time] … seems warped, buckled and bent out of shape … It is as if the passage of time has been creased and folded back upon itself, tugging the present through and beyond the future, making futures past; it bends our anticipations back into the immediate present and reveals them as decades-long-dead possibilities. In the Anthropocene, projections of the future have no purchase in the present. We are presented with scenarios that range from the disastrous to the catastrophic, and in each case the urgent contingencies they demand are a direct result of the choices, dreams, expectations—the daily carelessness—of dead or dying generations, laying an inescapable burden of necessity upon our children and grandchildren (2020).

This is bleak, to put it mildly. In this vision, the future has not simply been ‘eaten’ by the present, it has also been mangled and mutilated. However, the account of reimagination of, engagement with, and intervention in buried riverscapes around Łódź we offer in our study indicates that temporal counter-currents can occur. Even when the unlocking of submerged waterways proves problematic, such as the stream underneath the Manufaktura complex, it is notable that recognition of its existence resulted in a line of fountains within a square that brought the aquatic dimension back to a place frequented by families, shoppers and by workers on their breaks. The Piotrkowska Street mural symbolises many of these aspects, propelling the civic ship that symbolises the city’s riverine past out of the representational plane and into the present. In these manners, there is a reassuring aspect to symbolism and representation as forms of public hauntings. In evoking elements that precede the Anthropocene, they remind us that the latter may not totally inundate us. While global warming may still be a long way from being reined in by governmental and corporate action, local level reinvestments in environmental restoration are possible when sufficient thresholds of motivation are reached. In attempts to achieve these, heritage elements, symbols and associations are valuable resources that can be activated.

Notes

- Here we are referring to an approach developed by Russian Formalists such as Viktor Shklovsky and later theorised as the verfremdungseffekt by German dramatist Bertolt Brecht whereby familiar aspects of socio-economic-political values and interactions are represented on-stage in ways that make them appear as ‘strange’ to audiences and prompt them to question them. ⮭

- The latter term being the Indigenous Kanien’kéha name for the city. ⮭

- It is unclear whether the village was named after the river, or vice versa. ⮭

- Giorgio de Chirico was an Italian artist who founded the scuola metafisica movement in the early 20th century. His most famous works, such as ‘Mystery and Melancholy’ (1913) or ‘Turin Spring’ (1914), represent city squares and streets with distorted and dramatic perspectives. ⮭

- See for instance, those reproduced at: https://www.tattoodo.com/tattoos/370422 and https://sigil.art.pl/tattoo/lodz/. ⮭

- Sample of images on display at: https://sigil.art.pl/tattoo/lodz/. ⮭

- At time of writing (November 2023) the City of Łódź’s Department of Ecology and Climate Environmental Management Division is optimistic about gaining funding for this in 2024 and aims for construction work to commence in 2025 (Sztuka-Tulińska, 2023, pers. comm). ⮭

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Tomasz Dobrogoszcz and Agata Handley for their help and encouragement for our work on this project and to Aleksandra Sztuka-Tulińska (Deputy Director of the Environment Management Division, Department of Ecology and Climate, City of Łódź Office) and Andrzej Gagz (Sigil Tattoo studio) for responding to our research inquiries. Tomasz Fisiak would like to thank Ewa Brzezińska and Marek Majer for their company during the ‘river-hunting’ walks and their photographic help. Philip Hayward would like to acknowledge that his travel to Łódź in 2022 was facilitated by a Polish Ministry of Science research grant awarded to a team led by Dorota Filipczak.

Competing Interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

References

1 Adamczewska, I. (2023, July 28). ‘Jesteśmy rzecznymi sierotami.’ Maciej Robert tropi ślady po rzekach w Łodzi. Gazeta Wyborcza Łódź. Accessed 8 February 2024: https://lodz.wyborcza.pl/lodz/7,35136,30010068,lodzianiesa-rzecznymi-sierotami-spacerowywiad-z-maciejemrobertem.html

2 Ainiala, T., & Östman, J.-O. (2017). Introduction: Socio-linguistics and pragmatics. In T. Ainiala, & J.-O. Östman (Eds.) Socio-onomastics: The Pragmatics of Names (pp. 1–13). Amsterdam: John Benjamin. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1075/pbns.275

3 Armstrong, M. L., et al. (2002). College Tattoos: More than Skin, Deep. Dermatology Nursing, 14(5), 317–323.

4 Buchan, B. (2020). Anthropocene time. Arena 1. https://arena.org.au/anthropocene-time/

5 Derrida, J. (1994). Specters of Marx: The state of the debt, the work of mourning and the New International. (P. Kamuf, Trans.). London: Routledge.

6 Gan, E., et al. (2017). Introduction: Haunted landscapes of the Anthropocene. In E. Gan, A. Tsing, H. Swanson, & N. Bubandt (Eds.) Arts of living on a damaged planet: Ghosts and monsters of the Anthropocene (pp. G1–G14). Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

7 Gordon, A. F. (2008). Ghostly matters: Haunting and the sociological imagination. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

8 Hayward, P. (2017) Merlionicity Part II: Familiarity breeds affection. Journal of Marine and Island Cultures, 6(2), 75–85. DOI: http://doi.org/10.21463/jmic.2017.06.2.06

9 Hutchison, A. (2014). The Whanganui River as a legal person. Alternative Law Journal, 3, 179–182. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1177/1037969X1403900309

10 Jażdżewska, I. (2017). Murals as a tourist attraction in a post-industrial city: A case study of Łódź (Poland). Turyzm/Tourism, 27(2), 45–56. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1515/tour-2017-0012

11 Jędruszkiewicz, J., & Piotrowski, P. (2013) Past Industrial Traces of the Jasień River in the Tourism Space of Łódź. Tourism, 25(2), 37–45. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1515/tour-2015-0004

12 Kobojek, E. (2017). A small river within the urban space: The evolution of the relationship using the example of Łódź. Space-Society-Economy, 19, 7–19. DOI: http://doi.org/10.18778/1733-3180.19.01

13 Paphitis, T. (2020). Haunted landscapes: Place, past and presence. Time & Mind: The Journal of Archaeology, Consciousness & Culture, 13(4), 1–7. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1080/1751696X.2020.1835091

14 River Cities Network. (2023). RCN manifesto. Accessed 18 February 2024: https://www.rivercities.world/manifesto

15 Robert, M. (2023). Rzeki, których nie ma. Wołowiec: Wydawnictwo Czarne.

16 Sohidul Islam, M., & O’Donnell, E. (2020). Legal rights for the Turag: rivers as living entities in Bangladesh. Asia Pacific Journal of Environmental Law, 23(2), 160–177. DOI: http://doi.org/10.4337/apjel.2020.02.03

17 Stone, C. D. (1972). Should trees have standing? – Toward legal rights for natural objects. Southern California Law Review, 45, 450–501.

18 Szkurłat, E. (2015). Human – river relations at various stages of development of water front factory settlements in Łódź. Environmental & Socio-economic Studies, 3(4), 47–56. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1515/environ-2015-0073

19 Szpakowska-Loranc, E., & Matusik, A. (2020). Łódź – Towards a resilient city. Cities, 107, 1–14. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2020.102936

20 Talling, P. (2011). London’s lost rivers. London: Century Trade.

21 Tiller, K. J. (2007). The Rise of Sir Gareth and the Hermeneutics of Heraldry. Arthuriana, 17(3), 74–91. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1353/art.2007.0045

22 Toso, T., Spooner-Lockyer, K., & Hetherington, K. (2020). Walking with a ghost river: Unsettling place in the Anthropocene. Anthropocenes 1(1), 1–17. DOI: http://doi.org/10.16997/ahip.6

23 Wasilewski, J., & Kostrzewa, A. (2018). Syrenka tattoos: Personal interpretations of Warsaw’s symbol. Shima, 12(2), 144–162. DOI: http://doi.org/10.21463/shima.12.2.13